Several studies have shown that higher education can significantly contribute to economic development. This means that the more educated people are, the more knowledge-based and complex products and services can be produced (Feldman, 1999; Moretti, 2004; Audretsch and Feldman, 2004). However, public and private resources for higher education are limited and demand complex decisions regarding the locations and types of courses to offer. Different disciplines address different demands and bring different economic and social benefits. Moreover, limited funds imply difficult trade-offs between promoting excellence and knowledge diffusion, a critical problem in most countries, especially in countries with large levels of regional inequality like Brazil.

Romer (1986) showed that knowledge tends to have increasing returns to scale, which implies that bundling resources in centers of excellence may provide higher returns that can nurture economic development. However, in countries like Brazil, the large levels of structural heterogeneity and regional inequality undermine sustained economic development and lead to a series of political, social, and economic problems.

Promoting enrollment in academic fields that have a greater effect on economic development and attend local labor market demands is arguably necessary in countries with limited funds for higher education (Ortiz et al., 2020). Naturally, though, it is neither feasible nor effective to promote expensive courses, such as engineering or medicine, in all 137 mesoregions of the country. Instead, courses such as business and law are more likely to be offered in most regions, but may not necessarily be the main bottleneck for economic development.

At the same time, the location policy of higher education courses must also consider the spillover effects of human capital on neighboring regions. The effects of higher education investments are not limited to the municipalities where they take place, but also to their neighboring regions. NECODE researchers have applied methods of spatial autocorrelation and geographically weighted regressions (GWR) to reveal the spatial distribution of higher education and consider knowledge concentration and spillover effects. (to reveal the spatial concentration of human capital and higher education and verify the knowledge spillover effects.)

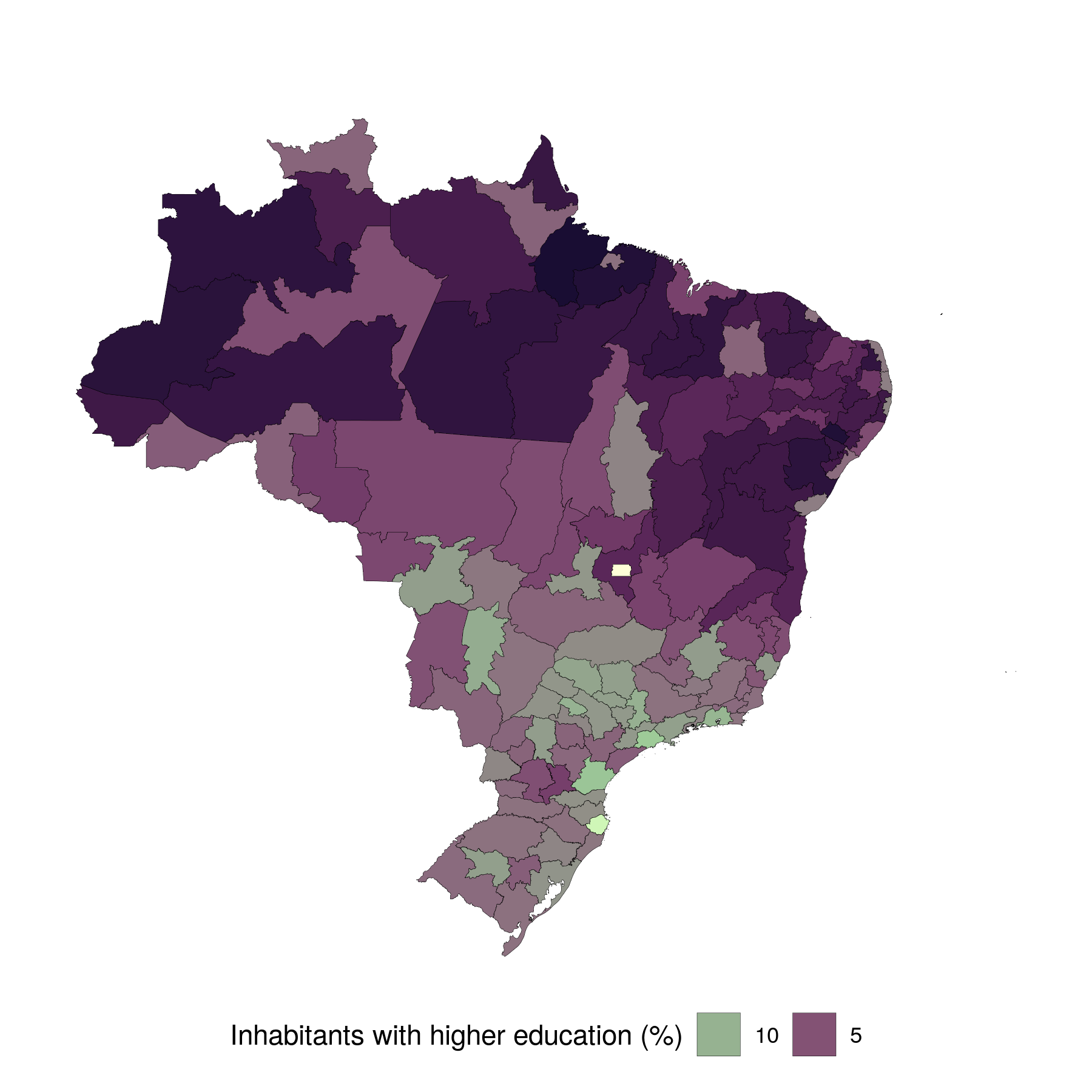

In Brazil, the proportion of inhabitants with higher education is highly concentrated, and we find high levels of socioeconomic divergence among neighboring regions. This may lead to mutual positive effects of knowledge spillover effects, where both benefit. Still, investments in core regions may also aggravate the problems of regional inequality. The figure below uses the 2010 census data to show the spatial distribution of the proportion of inhabitants with higher education at mesoregional level. Moreover, a Moran’s I coefficient of 0.46 indicates a notably high level of spatial autocorrelation (considering that this statistic ranges between -1 to +1).

Geographically weighted regressions (GWR) show that significant and positive effects of higher education on economic complexity can be observed heterogeneously over space (Viegas and Hartmann, 2022). However, these effects depend on the higher education field, as well as on the human capital stock of neighboring regions. Taking the spatial spillover effects into account, not only on the municipal, but also microregional and mesoregional levels, can help to promote more efficient and effective economic development policies.

Guilherme Viegas and Dominik Hartmann

References:

Audretsch, David B.; Feldman, Maryann P. (2004) Knowledge Spillovers and the Geography of Innovation. Handbook of Regional and Urban Economics, 4, 2713-2739. Available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=1504470

Balland, Pierre-Alexandre; Jara-Figueroa, Cristian; Petralia, Sergio; Steijn, Mathieu; Rigby, David; Hidalgo, César A. (2018) Complex Economic Activities Concentrate in Large Cities. Nature Human Behaviour. Available at: http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3219155

Feldman, Maryann P. (1999) The New Economics Of Innovation, Spillovers And Agglomeration: A Review of Empirical Studies. Economics of innovation and New Technology, 8(1-2). Available at: https://doi.org/10.1080/10438599900000002

Moretti, Enrico (2004) Estimating the social return to higher education: evidence from longitudinal and repeated cross-sectional data. Journal of Econometrics, 121(1-2), 175-212. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jeconom.2003.10.015

Ortiz, E. A., Kaltenberg, M., Jara-Figueroa, C., Bornacelly, I., & Hartmann, D. (2020) Local labor markets and higher education mismatch. IDB Working Paper Series IDB-WP-01115. Available at: http://dx.doi.org/10.18235/0002295

Romer, Paul M. (1986) Increasing Returns and Long-Run Growth. Journal of Political Economy, 94(5). Available at: https://www.jstor.org/stable/1833190

Viegas and Hartmann (2022) Higher Education, Knowledge Spillovers, and Economic complexity. Available at: https://repositorio.ufsc.br/handle/123456789/241843